Human beings are dramatically changing the surface conditions on planet Earth at an accelerating rate. One key aspect of this is pollution.

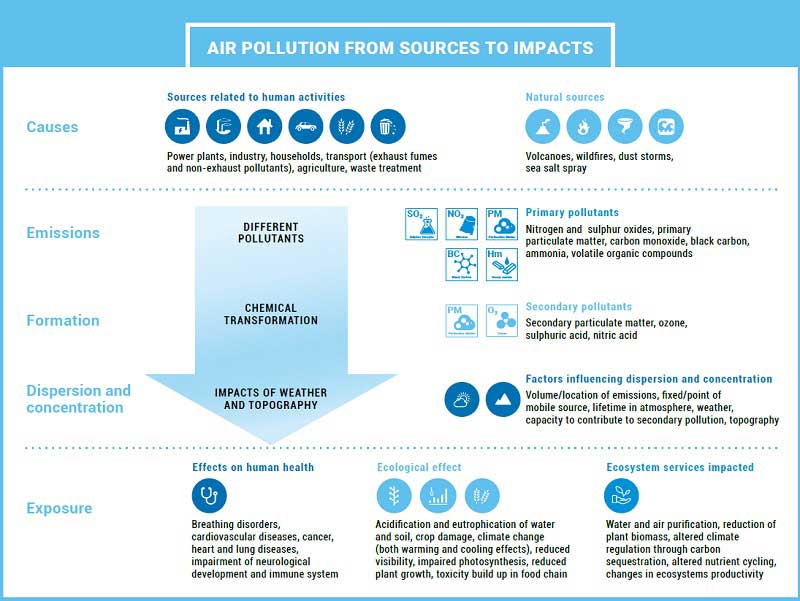

Our emissions of particles (PM2.5or fine particulate matter 2.5 that is an air pollutant) and ozone (O3) air pollution at ground level cause massive damage through breathing, which already accounts for some 8.79 million human deaths annually, about 15% of the global total. (European Heart Journal, Volume 40, Issue 20, 21 May 2019).

Plastic pollution soils the air, land, groundwater, and oceans, killing countless animals and causing cancers in humans. Emissions of greenhouse gases accumulate in our atmosphere and drive relentless heating of air, land and oceans. Through water expansion and melting ice, this heating raises sea levels, with loss of low-lying lands and salinization of groundwater.

Other land areas become too hot for human habitation, frequently devastated by extreme weather events, or infested with invasive pests or diseases. All this disrupts food production, thus aggravating undernourishment and poverty, and also causes the extinction of thousands of animal and plant species.

Are we sitting in the same boat?

Contrary to much trite rhetoric about how we are all sitting in the same boat without a Planet B, human beings are in fact very differently situated in regard to environmental degradation.

Affluent people in temperate zones may be barely affected and can further protect themselves with sophisticated air conditioning in their homes, cars and offices, and by purchasing organic food, sunscreen and indoor exercise equipment. Should these remedies still leave discomfort, they have ample relocation options.

Many poor people in tropical regions, by contrast, have no way at all to avoid an early death from malaria, malnutrition, cancer or heat exhaustion.

Similarly, dramatic discrepancies exist on the contribution side.

Electricity consumption in 2016 was about 160 times higher per capita in the United States (US) than in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) which moreover uses clean electricity from hydroelectric plants; with crude oil consumption, the ratio is 300:1.

(Editor’s note: In the 2018 key energy statistics of the International Energy Agency, the electricity final consumption in 2017 for the US was at 4,099 TWh, while that of DRC was 9 TWh. One TWh or terawatt hour is equal to one trillion watt hours or one billion kilowatt hours or one million megawatt hours.)

Really, rich individuals, with their yachts, private planes and helicopters, even manage to produce as much pollution as 100,000 Congolese.

Pollution is then not a shared problem, akin to a meteorite about to strike Earth, but a justice problem more akin to slavery. On the one side are those who have been causing the problem or at least benefiting from the activities that cause it, many of whom are content to continue business as usual for a few more decades. On the other side are those for whom pollution is an urgent emergency that undermines their human rights and threatens their very health and survival.

While surely not among the most evil human rights violations in history, environmental degradation may well be, or become, the largest in terms of the harms it inflicts.

Inadequate responses

The Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals are clearly inadequate for addressing environmental degradation at the speed required. They demand far too little from the affluent, and the efforts they do demand are often absurdly inefficient.

The Paris Agreement focuses each state’s attention on emissions within its own territory. Thus, a highly-industrialized state is considered to have made progress when goods consumed in it are now imported (so that the pollution associated with their production now occurs in some far-away poor country rather than domestically).

Similarly, we give such a state credit for closing a few fossil fuel-fired power plants at home, even though its firms are also building dozens of such plants in poorer countries, often with favorable financing from banks in that industrialized state or even from its government (export credits).

Correcting accounting flaws and promoting international cooperation

While it makes sense to give states a primary role and responsibility for avoiding environmental harm, such accounting flaws must evidently be corrected. States must be held accountable for the worldwide impact of what their governments, corporations, financial institutions and citizens do, not merely for what happens within their national borders.

Such comprehensive accounting would invite further efficiencies. An industrialized state could have a huge positive impact, for instance, by helping poorer states onto a green path of development.

It could make plans with African peers for how they can meet their rapidly growing electricity needs with cutting-edge installations drawing on solar, wind, tidal, geothermal, hydro and/or wave power. And it could offer such African states to pay the cost difference between such green installations and the tired default of coal-fired power plants.

In these ways, industrialized states could avert huge amounts of pollution at very low cost – or even at negative cost, if one also takes into account that, avoiding fuel costs, those green installations are much cheaper to run.

This kind of international collaboration could be strengthened by a reform in the way green inventions are rewarded and incentivized. When poor countries find that specific green inventions are patented and may be used only with purchase of an expensive license, they will be sorely tempted to resort to older, more polluting alternatives of the sort richer countries used decades ago. It would be much better if everyone anywhere could use a green invention for free, and its inventors were then rewarded from public funds in proportion to the pollution averted.

From patent-protected markups to impact-driven rewards

In this regard, there will be a need to rationalize climate prizes. Why not provide large-scale international prizes under the auspices of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to encourage the development of clean technologies?

Extrapolating from the idea of a Health Impact Fund “that delinks the price of drugs from the cost of research,” an Environmental Impact Fund (EIF) is proposed. This is an alternative reward system that departs from the current model conditioned on patent-protected markups to one that is conditioned on the ecological benefit of innovation and willingness of the innovators to give up their patent-protected markups.

This proposed alternative rewards would encourage innovators actively to promote the widespread and effective deployment of their innovation so as to enlarge its impact especially on the poor. An innovator would seek to earn more by helping users get the most out of his invention and by subsidizing its use for additional impact among the poorest.

By creating an Environmental Impact Fund, financed by the more affluent states, a large pool of reward money would be distributed each year among registered green inventions in proportion to the environmental impact that will have been achieved through their use in the preceding year. The EIF would promote innovation not just in power plants and factories but also in products that are widely used by the poor that are neglected by private businesses.

Charles Chilufya SJ is the Director of the Justice and Ecology Office of the Jesuit Conference of Africa and Madagascar. This article was slightly modified for this edition and first published in Jesuit European Social Centre.

Originally published on: EcoJesuitRelated Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.