An air of fear and uncertainty looms large over the presidential elections in Côte d’Ivoire as the country struggles to shake off its turbulent past. Numerous factors are critical in determining whether the elections have a peaceful or violent outcome for a country that has lived through two civil wars this century. The first bout of conflict lasted between 2002 and 2007. The second ravaged the country from 2010 to 2011.

This history is affecting the mood in the country in, direct as well as indirect ways.

The foremost direct effect is the question of the legitimacy of presidential candidates. These include two principal actors in the country’s past armed conflicts – Laurent Gbagbo and Guillaume Soro. Both are on the ballot, even though they’re both living abroad to avoid incarceration.

Gbagbo is currently living in exile in Belgium. The former president was acquitted of charges of war crimes by the International Criminal Court. But he remains under legal proceedings in Côte d’Ivoire, where he was tried in absentia and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Soro, the former president of the National Assembly, was also tried in absentia and also sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Given the roles, each of these men played in the civil wars that plagued the country in the past, their reemergence as presidential candidates is capable of reviving old divisions and animosities. These are capable of threatening the peace and development that the country has enjoyed since the end of the war.

Further complicating the tense political atmosphere – as evidenced by many protests which have already claimed some lives – is the fallout from President Alassane Ouattara’s decision to renounce his pledge not to run for a third five-year term.

Gbagbo lost to Ouattara in the 2010 election and had to be forcibly removed after refusing to hand over to the winner.

The question on everyone’s mind is: can the country’s fledgling democracy withstand these pressures? Or could tensions between political actors, and the lack of a substantive reconciliation since the last civil war which ended in 2011 after claiming the lives of more than 3,000 people, trigger a regression into conflict once again?

Lack of consolidation

The democratic nature of electoral competition is yet to be consolidated in Côte d’Ivoire. This is apparent from two angles.

The first is the heated political discourse which shows that the political parties are positioning themselves for a decisive confrontation. Rivals tend to be seen as enemies rather than adversaries. This gives the impression that the country is in a winner-take-all logic where electoral failure is not considered by any of the sides.

The second is continued lack of consensus around the role of the Independent Electoral Commission. The reform of the commission – endorsed by the National Assembly in 2019 – is not to the liking of the opposition, which considers it biased insofar as the president has appointed people close to him at its head.

The contestation has found its way into the courts. The NGO Actions pour la Protection des Droits Humains (Actions for Protecting Human Rights) filed suit with the African Court on Human and People’s Rights in 2014 against the government regarding the unbalanced composition of the members of the commission. The court issued a decision in the NGO’s favour.

A new decision by the African Court on Human and People’s Rights on reforming the commission has not resolved the dispute but calls on the various actors to continue political dialogue from less ideological standpoints.

A quick compromise between electoral stakeholders must be found on the issue of composition of the 15 members of local electoral commissions. The same is true of the other elements of the electoral normative framework, such as the Constitutional Council and the electoral code.

What’s at stake

The elections have some implications for the country’s economic fortunes. According to the World Bank, Côte d’Ivoire enjoyed a growth rate of 7.4% in 2018 and 7.2% in 2019. This ranks the country only second to Ethiopia in terms of growth on the continent.

This could evaporate if the country can’t reach consensus around the election. That includes, even at this late stage, the question of a postponement. It also includes resolving logistical organisation of the election as well as the disagreements on the powers and composition of the Independent Electoral Commission.

The Democratic Party of Ivory Coast, along with civil society groups, has issued calls for a postponement, warning that “the political climate is tense”.

Pre-election, election-related, and post-election violence are not inevitable. It will all depend on the will of the various political actors who are free to choose peace or violence. They can choose to settle their disputes either through legal and institutional channels or through extra-institutional channels that lead to violence.

Hopefully, the choice made will be in the interests of peace for the country.

Source: The Conversation

Related Articles

Select Payment Method

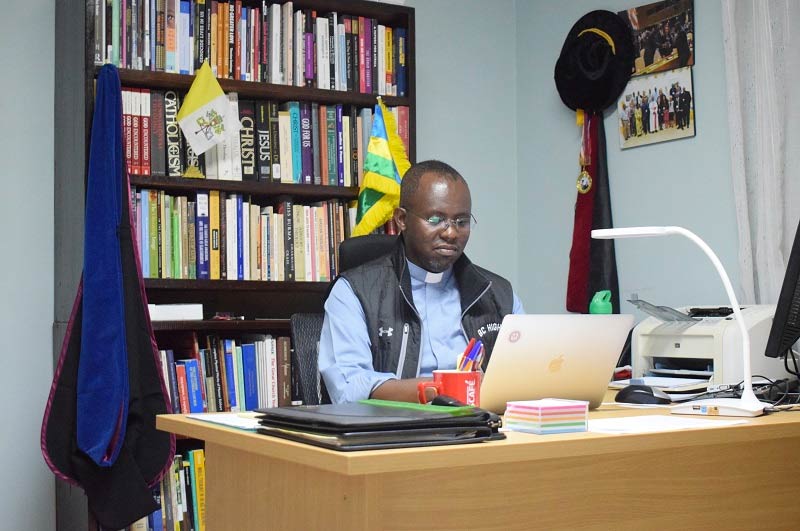

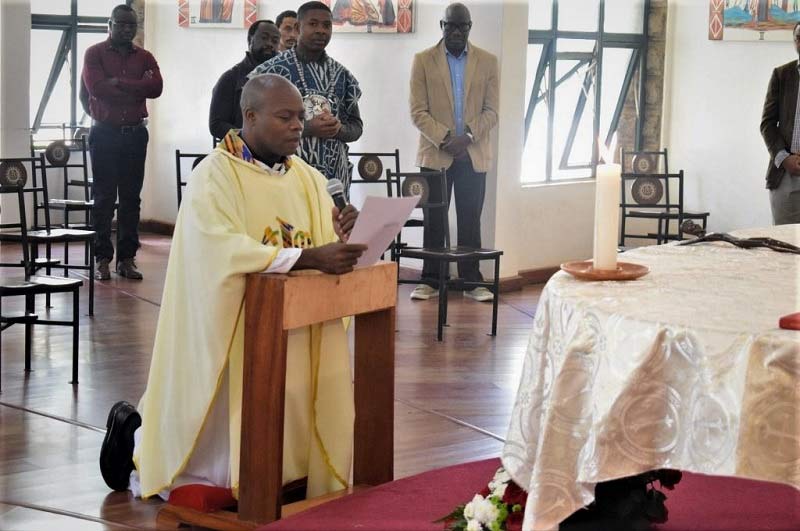

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.