Eerie. Visible. Sullen. Probing. No other adjectives could better describe the silence that now engulfs our relatively quiet neighbourhood of Angré every night. It is even more glaring in the section of the neighbourhood where our Jesuit theologate and community is located, because there are fewer houses and people there. This new air began on March 23; the day the first period of COVID-19 curfew decree took effect in Abidjan (from 9 pm until 5 am).

Since then, our streets are more deserted than they used to be. Greetings and pleasantries are exchanged with conspicuous distance. I sometimes wondered whether beneath those banters lie mutual suspicion of who might and might not be carrying the virus. Few residents move around with nose and mouth covered with different sorts of masks. Every night, in the days when the virus was still only in Wuhan, an unsolicited sermon from a nearby church and a random secular music from a near-by marquis saturated our airspace, leaving me sometimes — and perhaps my Jesuit brothers — conflicted.

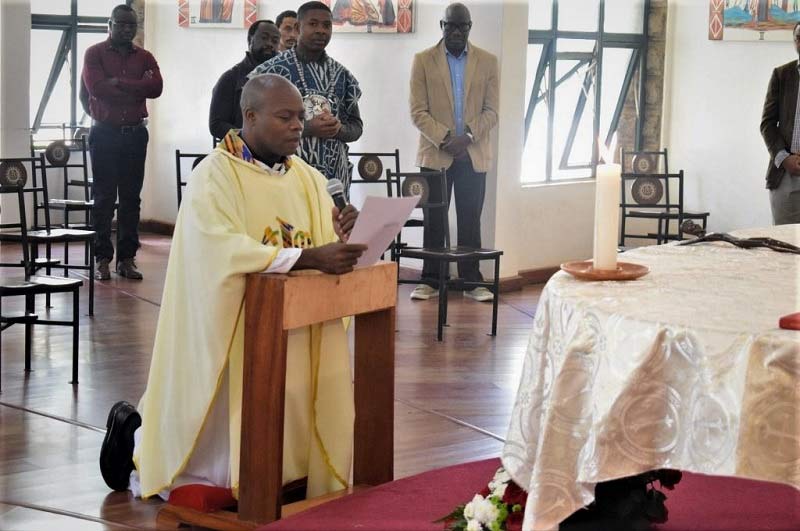

None of these is happening as I sat quietly in our semi-dark, cube-like chapel. The Holy Thursday liturgy was about to begin and our diligent sacristans paced the sanctuary to ensure everything was in place. Soon about sixty Jesuits will begin trickling into the chapel, and will sit one metre from each other. In the meantime, in the surreal silence of the night my mind raced fast and furious, assailed by thoughts and questions. How much more must we wait for a cure? How many more sleepless nights await Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus and his team? What are African leaders doing? What if Wuhan had not existed? I imagined the serenity and chaos cohabiting in selected medical labs; the sacrifices of doctors, nurses and other frontline workers; and people wearing nose/mouth masks and holding placards that says “Never Again!” on COVID-19 memorial day.

This train of thoughts gave way for another when the rector of my community, Fr Jocelyn Rabeson SJ, ended his homily by saying: “le sacerdoce c’est l’amour” (“priesthood is love”) repeatedly. Certainly, Christ’s institution of the priesthood is grounded in the same love upon which his acceptance of the redemptive mission for humanity is built. In the Second Week of the Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius offers an imaginative colloquy among the Divine Persons. It culminated in a decision that Christ will embark on a journey of redemption that can only be seen as love-motivated. It is only in such motivation that priests would continue to offer sacrifice of Bread and Win. But it was the idea of how acts of love animates the community in moments of crisis that lingered on my mind. And, not long, I began thinking of COVID-19 as a parable of the communality.

I am aware of a sense of personal vulnerability in the community after Abidjan recorded its first case of the virus. It was also impossible to end a conversation with reference or mention of COVID-19. Yet, I’m aware of a communal sense of vulnerability. A new realization impresses itself: our vulnerability does not cancel out our oneness in the Body of Christ. Not as some thrilling theological notion, but as a pervasive reality. A good part of this corporality is a closer attention to how one embodies the other, for the health of one affects the rest. We may begin to fathom the mysterious truth of Paul’s words to the Colossians: “I am completing in my own flesh what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ for the sake of his Body, the Church” (1:24). Our love for the group to which we belong, says the Irish statesman, Edmund Burke, is the first principle from which we proceed toward a love to our country and to mankind.

My thought on COVID-19 as a parable of the community was not limited to my Jesuit community. It incorporates the idea that, as Benedict XVI puts it in Caritas in Veritate, “the human race is a single family”. The principle of community is inherently a normative state of being.

Since the virus left the walls of China, the country has been the subject of blame politics. After all, some have argued, COVID-19 is Chinese-made. China — though unintentionally — has also reinforced the notion of global-community, in a way that ridicules, afresh, our spatial and political boundaries. The opening paragraph of Robert Ludlum’s bestselling novel, The Bourne Supremacy, undermines the geographical boundaries of Kowloon, an urban are of the Chinese city of Hong Kong, and suggests that a common “spirit” of survival surmounts all limits. There is no doubt that there is an ongoing collective quest for a global solution to a global problem. The virus, the polemics it has raised, and the solidarity it continues to incite, therefore, could be seen as a metaphor for the need for a renewed vision of a world-community.

The pandemic, it seems to me, offers us an apt opportunity not only to reaffirm and refine but also to extend our sense of the spirit of community in light of the present exigencies and thereafter. It calls us to undermine the divinization of the “I/Me” and embrace the “We/Us”. Not to a communitarian order that submerges the person into the mass but the kind that Richard Weaver calls “social bond individualism” achieved through what, in Quadragessimo Anno, Pius XI described as a “sane corporative system”.

The metaphysics that grounds the notion of community that I’m imagining carries significant implications. At all times, the metaphysics that grounds the notion community — small or great — ought to be governed by charity, love and truth. It ought to transcend particular times and places and achieves its completion in a state of union with God. With such anthropology of community that traces its root to and see its ultimate finality in God, economic-triggered, racial and political division becomes absurd and impossible from its own monstrosity. Extreme meliorism, too, becomes tempered by the sense of God’s continuous participation in the world he created.

Nights at Angré are still eerie. An unseen blanket of silence still falls on us like a spell and the fear of COVID-19 still hangs in the air. Yet, mutual love and communal effort to adapt to this difficult times still remains a source of hope in my community, for hope — like charity, love and truth — given and received, is normative to community life at all seasons of life.

Related Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.