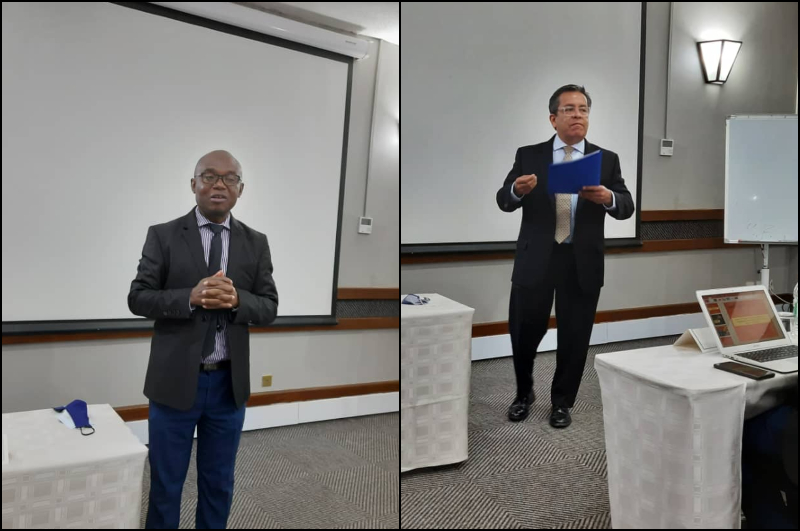

The JENA Director, Fr Charles Chilufya. S.J. and the JENA Global Policy and Advocacy Officer, Fernando Saldivar, S.J joined Silveira House on 6th May 2021 at the Holiday Inn Hotel, Harare to deliver a workshop on Tackling Illicit Financial Flows in Zimbabwe.

Generally, illicit financial flows is an umbrella term for a broad group of illegal cross-border economic and financial transactions. They usually involve the transfer of money through illegal means such as corruption, criminal activities, and efforts to hide wealth from a country’s authorities. The outflows of money from Africa increase inequality and have humanitarian consequences as they hinder the capacity of governments to finance social service provision, development, and poverty reduction. Therefore, they severely and negatively affect the most vulnerable groups such as women, youths, and those with disabilities, and the poor in general. This is why JENA is concerned about the phenomenon.

Recently, the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in December 2019 has worsened the situation as most illicit exploitation of and trade in natural resources in most developing countries like Zimbabwe went unchecked due to national lockdowns instituted by governments as a measure to combat the pandemic.

Most of the illicit flows of money out of Zimbabwe come from the extractive sector. Therefore, the workshop highlighted the fact that though they experienced at the onset of the pandemic last year, international commodity prices have generally gone up during the latter part of 2020, with metals such as gold and platinum group of metals (PGMs) that Zimbabwe produces registering record-high prices. Despite all these positive developments in international prices and record-high profits by major resource companies, Zimbabwe has failed to reap the full benefits most importantly because of illicit financial flows. Consequently, this has raised discontentment and frustration among policymakers, donors, civil society organisations, and the general citizenry in the country.

The workshop heard that on the basis of the huge potential that lies in the mining sector, the government of Zimbabwe through the Ministry of Mines and Mines Development launched an ambitious US$12 billion mining economy by 2023, which is a 312% increase from the US$2.91 billion in 2019. However, the possibility of achieving this target will remain a pipe dream for Zimbabwe if rampant IFFs within the mining sector are not checked. For instance, in September 2020, the Minister of Home Affairs informed the nation that the country was losing an estimated US$100 million worth of gold every month due to rampant smuggling through the country’s porous points of entry, and this translates to US$1.2 billion per year. Gold export earnings decreased from US$1.3 billion in 2018 to US$946 in 2019, perhaps an ominous sign that the gold smuggling problem is festering. As hinted out already, what this means is that as the cash illegally pours out of the country, the government is left with no means to buy medicines, finance social protection, and other essential services at a critical moment like the current crisis we are facing.

Finding Solutions: How Can Zimbabwe Address IFFs in the Extractive Sector?

Against this background, the Workshop proposed to the MPs a different way of taxing the extractive sector that would give Zimbabwe or any African country more control in the taxation process. The current tax regimes leave things in the hands of corporations who have every incentive to hide revenues and incomes for purposes of paying lower taxes.

Zimbabwe and other developing countries in Africa should not tax the profits of natural-resource extracting firms at all. They should instead simply charge for a carefully formulated right of natural-resource extraction. This charge could be called a tax or fee or royalty, as convenient; and it should be determined through a competitive bidding process. The lots to be auctioned could be defined through spatial, temporal, and (optionally) quantitative limits. Bids for particular lots could be formulated to take account of the quantity extracted and the relevant world market price during the custodial period. Bidders should be free to formulate their bids within a straightforward grid of parameters and be free also to submit several bids for the same lot (differing perhaps in their sensitivity to the quantity extracted or to the evolution of the world market price of the extracted resource). An independent expert committee should determine which bid promises the best revenue stream for the selling state.

The reason for giving firms the option to enter several competing bids is to elicit information about their attitudes to risk and predictability. For example, a firm may enter one bid involving a fixed charge per resource unit extracted and another bid involving a variable charge tied to the average world market price during the contract period. A comparison of these two bids reveals the company’s degree of aversion to risk from a decline in world market prices. The selling government can then accept the fixed-charge-per-unit bid if and only if it determines that it is more capable of shouldering this market-price risk than the company is revealing itself to be. Similar considerations apply to other kinds of risk, for instance, the risk of quantitative shrinkage. If the selling government anticipates that it will have a hard time ensuring that extracted quantities are accurately measured and fully paid for, it may prefer a bid that offers a charge that does not depend on quantity (allowing the bidder, for one fixed payment, to extract all it can from the relevant site in the allotted time period). All such discrepant risk preferences between seller and buyer provide opportunities for additional efficiencies that increase the cooperative surplus generated by their transaction and hence the revenues the selling state can capture from it.

See full proposal {HERE}

Related Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.