The impact of COVID-19 has been felt globally with severe human costs. But on the social and economic fronts, it has had a worse impact on poorer countries in regions like Sub-Saharan Africa. One particular Sub-Saharan African country still reeling from these impacts is Zambia. This disease-induced social and economic shock could not have come at a worse time than now for Africa’s second-largest copper-producing economy awash in increasing poverty, worsening climatic conditions, a widening budget deficit, and facing a debt crisis. Zambia, like other African countries, is faced with plunging revenues and fast increasing borrowing costs as investors seek relative safety. Zambia does not even have the funds to fight the pandemic and shore up its economy.

Both the current economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic are placing Zambia between a rock and a hard place forcing hard choices on the struggling Southern African economy. The Zambian government has to choose between paying foreign creditors or keep its citizens from dying due to lack of medicine and other essential equipment in hospitals needed to ensure robust health systems in this difficult moment.

Zambia’s average public debt has been rising since 2011 when the ruling Patriotic Front (PF) party won the elections, unseating an incumbent government. Until then, Zambia limited its borrowing and had a booming economy that grew 6-7% annually between 2005 and 2011. When the ruling PF came into power the external debt stood at only $1.9 billion equivalent to only 8.4% of GDP. Zambia’s debt now stands at approximately $12 billion, approximately 51% of GDP. Zambia has in fact become the first COVID-19-related default in Africa as private holders of its $3 billion of Eurobonds voted two weeks ago, on Friday 13th November, against the country’s proposal to suspend for six months the payment of a $42.5 million coupon at the expiry of the grace period on that Friday.

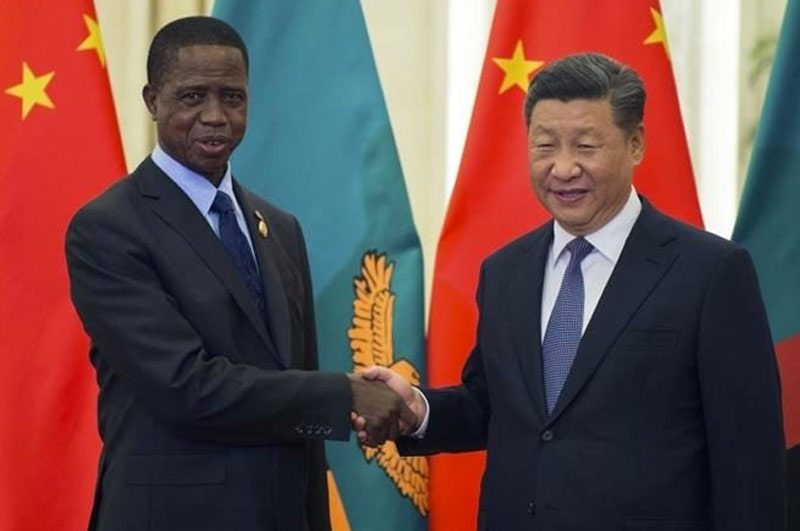

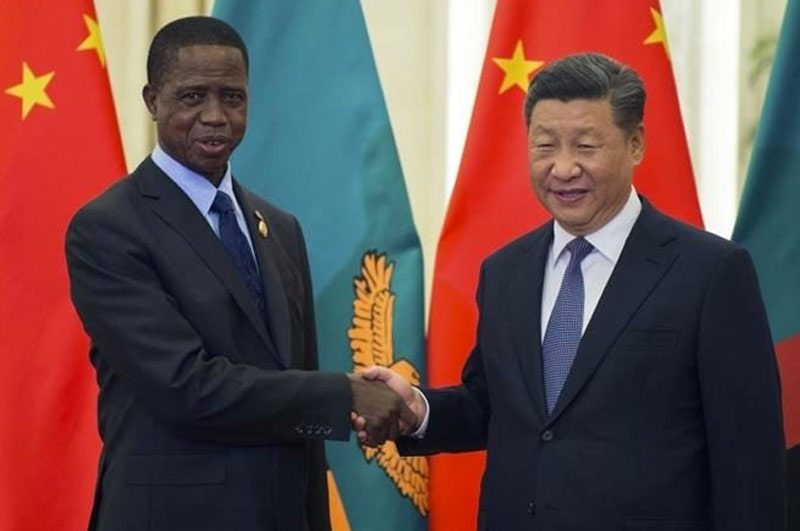

This debt crisis is not a new one for the Zambian government. In 2005, during the previous big round of debt relief for the continent, the IMF and World Bank deployed the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, which allowed for the cancellation of foreign public debt of recipient countries, that included Zambia, of about 100% of GDP. However, at the time, most of that debt was owed to Western governments and multilateral organisations, like the IMF and World Bank. This time, Zambia’s major bilateral creditor is China. But unlike the private creditors, China announced it will delay interest and loan repayments on its loans from May to December 31. This should technically grant Zambia some four to five weeks of relief.

Even though there are already increasing calls for suspension of all debt payments this year for developing countries, there is still trouble ahead for Zambia. The problem is that Zambia, like many other African countries, collects relatively little revenue for financing development due to limited capacity for optimal revenue collection and for stemming revenue losses through illicit financial flows (IFFs). Even though the current commentary on Zambia’s default focuses exclusively on the government’s sovereign borrowing, Zambia has experienced massive outflows of private wealth over the past fifteen years. These outflows are said to have reached peaks of almost 20% of GDP in 2012, 15% of GDP in 2015, and over 7% of GDP as recently as 2017 thereby acting as a countervailing force against the gains from the commodity boom of 2003 to 2011.

Zambia has substantial natural resource endowments, mainly copper, whose exploitation, mostly for export, is typically handled by large Northern multinationals that transmit a share of their sales revenues to the relevant state, typically in the form of taxes. There is much debate about whether this share has been fair. Critics contend that corporations typically earn vastly more than what would be necessary to get the job done, that they pocket huge windfall profits at the expense of the host countries like Zambia. This critique is especially vexing in view of the dire poverty that burdens Zambians and so many other citizens of these resource-rich countries, such as Niger, DR Congo, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Tanzania, and Nigeria.

As the recent UNCTAD’s Economic Development in Africa Report 2020 shows, African countries like Zambia are in fact net creditors rather than debtors. The Report demonstrates that comparing Africa’s total external debt stock to losses in illicit financial flows, many African countries are in fact “net creditors to the world”. For example, the enormous sums Zambia has lost in IFFs relative to the $3 billion of sovereign bonds currently in default, would give a different perspective to the rise of sovereign borrowing by Zambia. A lot of Zambia’s wealth is now offshore. As outflows of wealth continue, Zambia and other African countries continue to borrow in a desperate attempt to keep the finances afloat. Who suffers in the end? It is ordinary Zambians that are now paying the price as they go to hospitals without medicines they badly need and as children go to school without the needed supplies to aid learning. The current international financial architecture that facilitates massive outflows of wealth hardly has any credibility. Zambia and other countries need more than just debt relief, they need justice via a new international economic model that, as Pope Francis says, gives life rather than kill.

Charles B. Chilufya is the Director of the Justice and Ecology Office of the Jesuit Conference of Africa and Madagascar.

Related Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.