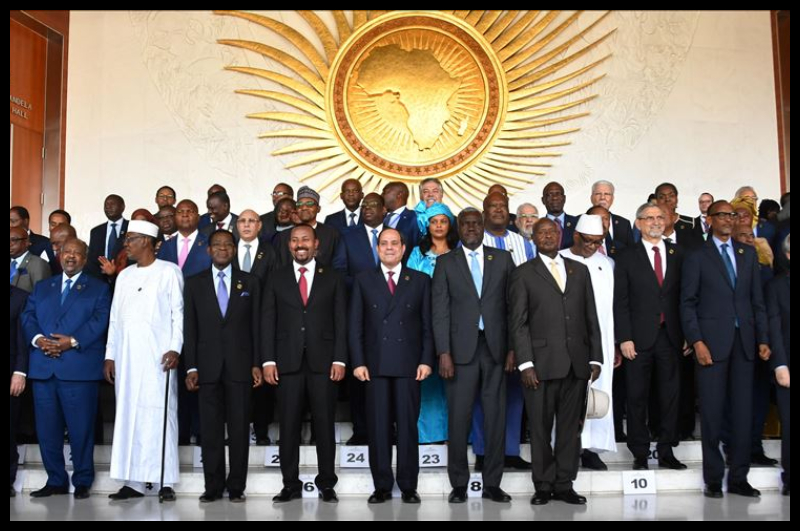

The Sixth African Union – European Union (AU-EU) Summit concluded in Brussels on 18 February 2022 after two days of deliberations between leaders from the two continents.

Given that this marked the first occasion for AU and EU heads of state to come together since 2017 there were high hopes on the part of African leaders and civil society groups that the summit would focus the world’s attention on the critical challenges to development Africa continues to face, particularly in light of both the renewed sovereign debt crisis and the pressures here of simultaneously responding to climate change. Additionally, as the summit itself had been repeatedly postponed on account of the pandemic, there was hope that Africa’s challenges in responding to COVID-19 would take center stage. While providing a modicum of progress, the tepid outcome of the summit leaves several key issues in regard to African-European relations unaddressed.

We can measure the success of the summit by reading its closing document, “A Joint Vision for 2030.” While the document is certainly less ambitious than was hoped, there are a number of areas that provide a foundation for more aggressive action in the days ahead. The first, and most critical, is in regard to vaccine production and distribution. Recognizing that “fair and equitable access to vaccines” is the life-and-death challenge facing Africa as a whole, the EU committed itself not only to providing at least 450 million more doses immediately, but also to expanding the capacity of African manufacturers to produce vaccines. Although not mentioned, sharing vaccine technology with African labs could lead to major breakthroughs in treatments for endemic diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, which overwhelmingly strike the poorest of the poor. Additionally, fact that the document recognizes that the pandemic has had an unprecedently severe macroeconomic impact on African states, both parties call for the IMF and its member states to make increased use of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to aid the continent’s recovery.

Moreover, there is some hope in the document’s text that the EU is pledging itself to rethinking the framework of global finance and international relations in a way that amplifies Africa’s voice and is better representative of the continent’s share of the world’s population. Most encouraging in this regard is the section discussing multilateralism. Here, EU leaders commit themselves to seeking reform of the UN Security Council and the World Trade Organization. Given that after Brexit, France remains the only permanent member of the Security Council in the EU, we can read this as a specifically French commitment to champion reform of UN bodies.

However, the subject of France brings up one of the thorniest issues that the Joint Vision does not address – the political, military, and humanitarian catastrophe in the Sahel. Although there is a section dedicated to peace and security, there is no mention at all of Operation Barkhane or France’s withdrawal of its troops from Mali in response to the impasse between Paris and the Malian coup leaders. In fact, while on the subject of coups, one might be forgiven for thinking that democratic institutions throughout Africa were robust and the toppling of governments in Guinea, Chad, Mali, and Burkina Faso had never taken place, given that the document makes no reference to any of them. This is a sharp oversight considering the risk of political violence from upcoming elections in Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa. A joint AU-EU statement on election transparency could have helped to focus global attention on the need to not only report on what is happening here on the ground, but to lend support to civil society and human rights activists. The failure to discuss issues related to the recent coups, or to strengthening democratic institutions more generally, reflects a willful and dangerous blindness on part of both AU and EU leaders.

While nowhere nearly as ambitious as the situation in Africa calls for, particularly in light of the ongoing pandemic and the severity of the economic crisis, the AU-EU Joint Vision for 2030 does give us a framework to continue pressing Europe and the rest of the Global North for the reforms and policy prescriptions that Africa desperately needs. The burden rests on African shoulders not to sit content with this modest vision and to press with an ever louder voice for what the people of the continent need in order to begin even thinking about what the post-pandemic world will look like here. The fruits of the Sixth AU-EU Summit are modest, but that is no reason to be equally modest in articulating what the situation on the ground here in Africa calls for.

Fernando C. Saldivar, S.J. is the Global Policy and Advocacy Officer at Jesuit Justice and Ecology Network Africa (JENA).

Photo by Anadolu Agency.

Related Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.